Thompson Park NY

1. Conceptual Design and Amenities

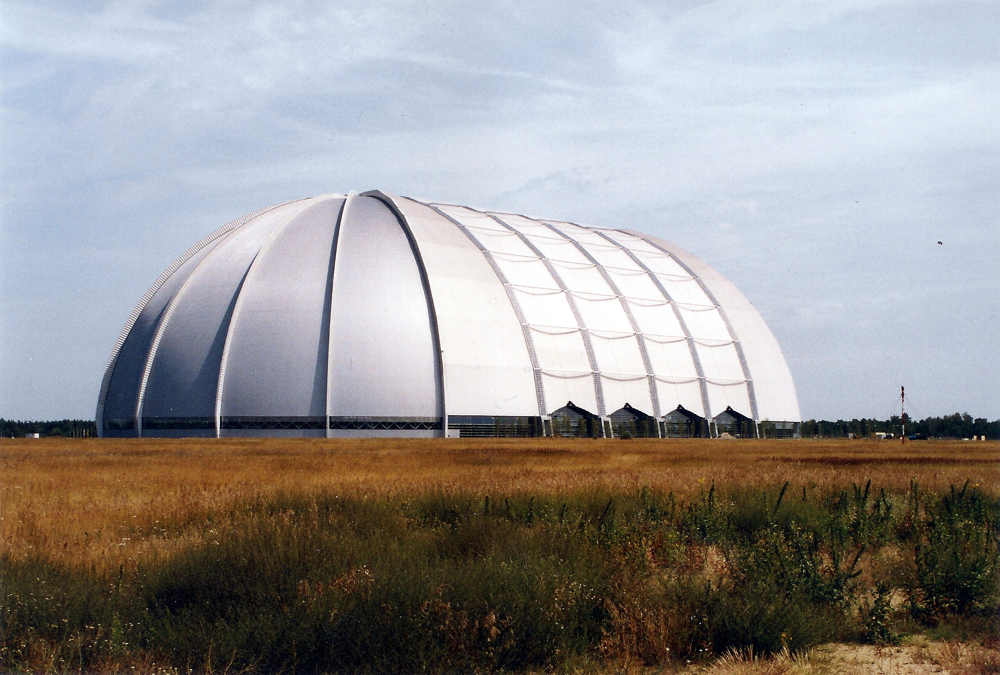

A conceptual dome structure (inspired by Tropical Islands in Germany) could house the indoor tropical park. This type of free-span enclosure would ensure a stable, warm climate year-round, even amid Upstate New York blizzards. The complex would be built as an all-season enclosed environment maintaining a tropical ~80°F (26°C) temperature and lush humidity inside, regardless of outdoor weatheren.wikipedia.org. The architectural design should minimize impact on Thompson Park’s natural beauty – for example, a dome or atrium with transparent panels (ETFE or glass) could be partially earth-sheltered or nestled into the park’s topography, preserving sightlines. City leaders have emphasized that new park attractions must not spoil the park’s historic characterwwnytv.com, so the building’s form would be organic and visually harmonious (perhaps with green-tinted glass, natural stone accents, and landscaping around it). By using a geodesic or tension-membrane dome (similar to the former airship hangar now housing Tropical Islands), the structure can span a large area without interior columnsen.wikipedia.org, creating an open tropical oasis under one roof.

Inside the facility, visitors would find a tropical paradise filled with water attractions and botanical features:

- Wave Pool & Sandy Beach: A large wave pool (with a machine to generate gentle surf) forms the centerpiece. This pool would mimic a tropical lagoon with a sandy beach perimeter, palm trees, and maybe a backdrop of painted sky or LED screens for ambiance (much like Tropical Islands’ 140m “Tropical Sea” pool lined by a 200m beachen.wikipedia.org). Guests could swim or even body-surf on artificial waves, then relax on lounge chairs under real tropical foliage.

- Lazy River: A slow-flowing lazy river winds through the complex, meandering through the indoor rainforest and past waterfalls. Guests floating on tubes would drift under the canopy of exotic plants and alongside rock grottos and maybe even faux ruins or animal sculptures, creating an adventure atmosphere.

- Indoor Waterslides & Play Areas: A towering waterslide structure would offer multiple slides – from high-thrill tube slides to family-friendly open-air slides – all contained safely within the dome. For example, a slide tower could start near the dome’s ceiling for a long ride down. Additionally, a children’s splash zone with small slides, water sprayers, and a tipping bucket provides safe fun for kids. (Many successful indoor waterparks like Kalahari feature dozens of slides and play features; Kalahari’s Poconos resort, for instance, spans 220,000 sq ft with numerous slides and poolsen.wikipedia.org.)

- Tropical Botanical Garden: A key differentiator of this complex is the integration of a living botanical garden. Thompson Park’s complex could include the world’s largest indoor rainforest in New York State, echoing Tropical Islands’ indoor rainforest with 50,000 plants (600 species)en.wikipedia.org. Winding walking paths would lead through lush vegetation – palm trees, banana plants, orchids, and even a butterfly garden or tropical bird enclosures (for example, small parrots or finches) to enhance the atmosphere. Educational signage can teach visitors about the plants and conservation, aligning with the park’s nature theme. The garden would not only be aesthetic but also help purify air and regulate humidity.

- Year-Round Amenities: Because it’s a public-private hybrid, amenities can cater to both daily local users and tourists. Facilities like locker rooms, showers, and family changing areas would be provided for day visitors. A spa and sauna section (perhaps styled as a Balinese or Nordic spa fusion) can offer hot tubs, steam rooms, and massage services for adults – Tropical Islands added a large tropical sauna/spa complex, recognizing demand for relaxation spacesen.wikipedia.org. Dining options would include a café and a themed restaurant (perhaps a rainforest café or a tiki bar) inside the dome so guests can dine in the tropical atmosphere. Retail space for souvenirs or swim gear would generate extra revenue.

To enable year-round operation even during heavy snowstorms, the building must be engineered with a sturdy roof and backup systems. A high-strength insulated roof (potentially a steel frame with tensioned fabric or polycarbonate panels) can withstand snow loads; alternatively, a retractable roof panel system could be considered to let in sun on clear days and close during storms. Power backup (generators or on-site renewable energy storage) would ensure climate control and lighting never fail, keeping the park open every day of the year (Tropical Islands, as a reference, is open 364 days a yearen.wikipedia.org). In winter, visitors could have the surreal experience of sitting on a warm indoor beach gazing out at falling snow through transparent sections of the dome.

Crucially, the design will take advantage of Thompson Park’s existing features where possible. The park’s “underutilized west side” has already been identified for new attractions in the city’s master planwwnytv.com – this area could host the new complex with minimal disruption to the popular picnic and zoo areas. If there is a decommissioned old reservoir or unused concrete pad in the park (noting the city plans to replace a leaking reservoiryahoo.com), that site might be repurposed for the foundation or water supply for the complex. By building on previously disturbed land, we preserve more green space. Overall, the conceptual design blends recreation, nature, and cutting-edge architecture to transform Thompson Park into a tropical haven that locals can enjoy any day and that becomes a must-visit attraction for tourists.

2. Case Studies of Successful Tropical Indoor Parks

To ensure the Thompson Park tropical complex is world-class, we can draw lessons from similar successful indoor water parks and tropical resorts around the world. Two notable case studies are Tropical Islands in Germany and Kalahari Resorts in the U.S., which demonstrate the viability of large-scale indoor water parks in colder climates and offer design and business insights.

Interior view of the “Tropical Sea” wave pool and beach at Tropical Islands Resort in Germany. The former airship hangar encloses a massive tropical environment with pools, sandy beaches, palm trees, and even a painted horizon to simulate an island atmosphere. Tropical Islands Resort (Brandenburg, Germany) is one of the most impressive analogues. Housed in a repurposed Zeppelin hangar (the Aerium) – the world’s largest single-span hall – it opened in 2004 and remains the largest indoor water park in the worlden.wikipedia.org. Despite being in the temperate climate of northern Germany, Tropical Islands maintains a balmy 26°C (79°F) and 64% humidity inside year-rounden.wikipedia.org, enabling a genuine tropical experience even during snowy winters. Key features of Tropical Islands include a huge indoor rainforest (50,000 plants, forming the largest indoor rainforest anywhereen.wikipedia.org), a 140m-long tropical lagoon pool with a 200m beachen.wikipedia.org, waterslides, and themed zones representing Bali, Thailand, Samoa, etc. It even added an outdoor pool zone for summertime (though the indoor facilities alone suffice in winter)en.wikipedia.org. This facility proves that with the right enclosure and climate control, a true tropical environment can be created in a cold region. It also shows the drawing power of such a concept: Tropical Islands can host up to 8,200 visitors per day and employs ~600 staffen.wikipedia.org, indicating significant job creation and tourism impact. One important lesson from Tropical Islands is the initial challenge of location – in its early years, attendance was below projections (~600,000 visitors in the first year vs. 1.25 million needed for break-even) and the resort lost moneyen.wikipedia.org. The remote site and limited local population were factorsen.wikipedia.org. They responded by adjusting ticket pricing and adding overnight accommodations to extend visitors’ stays, which improved attendance; by 2008 the park turned its first profiten.wikipedia.org. This underscores that Watertown must plan for broad visitor appeal (including marketing to tourists from beyond Jefferson County, e.g. Syracuse, Ottawa/Montreal in Canada, etc.) and possibly incorporate lodging or partnerships with hotels to maximize economic viability. Tropical Islands also teaches us about sustainable design: they discovered some plants struggled without natural UV light, so they installed a 20,000 m² special UV-transparent ETFE foil window in the dome to let in sunlighten.wikipedia.org. This innovation greatly improved plant health and reduced artificial lighting needs. For Thompson Park’s complex, using similar transparent ETFE panels in the roof would allow real sunlight to nurture the indoor forest and warm the space, reducing energy costs. Tropical Islands’ success (now owned by Parques Reunidos and a major tourist destination) illustrates that a tropical indoor paradise can thrive as a public attraction with the right mix of amenities, constant innovation, and initial public support (notably, the state of Brandenburg subsidized €10 million of its initial costen.wikipedia.org, a public-private boost we can emulate).

Kalahari Resorts (Wisconsin Dells, Sandusky, Pocono Mountains, etc.) provides another model, especially on the business and resort integration side. Kalahari is a privately-run chain of African-themed indoor water park resorts that has built some of the largest indoor water parks in the U.S. (the Kalahari in Round Rock, TX is 223,000 sq ft, currently America’s largest, and the Pennsylvania Poconos Kalahari is 220,000 sq ften.wikipedia.org). These resorts are located in regions with cold winters (Wisconsin, Pennsylvania) yet operate year-round, indicating robust design and market demand. A few takeaways from Kalahari’s approach that could inform the Thompson Park project:

- Resort & Convention Model: Kalahari typically includes a large hotel and convention center alongside the indoor water park. This drives multi-day stays and mid-week usage via conferences. For Thompson Park, a full hotel on park grounds may not be appropriate (since it’s a public park), but partnering with local hotels or encouraging a nearby private hotel development could capture more tourist spending. Alternatively, a small lodge or cabin accommodations on the park periphery (perhaps eco-friendly cabins) could be a compromise to allow some overnight stays without dominating the park. The key is to extend visitor length of stay beyond a single afternoon.

- Public-Private Financing: Many Kalahari projects have benefitted from local government incentives despite being private. For example, the planned Kalahari in Spotsylvania County, VA (opening ~2026) secured a performance-based deal where future tax revenues help finance the project (through Virginia’s Tourism Development Financing Program)spotsylvania.va.us. In that case, the county approved a TIF-like arrangement: once open, a portion of the resort’s sales tax is rebated to pay off the developer’s loans, meaning no upfront grant but a public-private partnership that shares future gainsspotsylvania.va.us. Spotsylvania also created a special tax district and offered infrastructure support, recognizing the huge economic impact expected. The project is 1.38 million sq ft with a 900-room hotel, 267,000 sq ft indoor waterpark, 156,000 sq ft convention space, 10-acre outdoor park, and promises ~1,548 jobs (805 full-time, 743 part-time)spotsylvania.va.usspotsylvania.va.us. In return, it’s projected to generate $7 million in annual tax revenue beyond the incentives and become the single largest taxpayer in the countyspotsylvania.va.us. This case study is instructive: it shows that municipalities are willing to invest or forego some tax revenue to attract a large-scale water park resort, because the net economic benefits (jobs, tourism, taxes) are so significant. For Watertown’s plan, a more modest scale is likely (perhaps no on-site convention center), but we can still pursue state/city support given the potential economic transformation (see funding section below). The Kalahari example also highlights how important job creation and tourism dollars are in making the case to public officials and citizens.

- Attractions and Operations: Kalahari and similar indoor parks (e.g. Great Wolf Lodge chain, Aquatopia at Camelback Resort) have refined the mix of attractions to maximize family appeal: wave pools, lazy rivers, big slides, surf simulators, kiddie areas, etc., paired with arcades, food courts, and retail. They often rotate new slides or attractions every few years to keep the park fresh. For Thompson Park, adopting a similar mindset of continual improvement and offering something for every age group will drive repeat local visits and long-distance travelers. The safety and staffing protocols at these parks are also worth emulating – e.g. certified lifeguards, robust water filtration, and indoor air quality control (proper ventilation to handle pool chlorine humidity is a must). We can consult experts from these existing parks during planning to ensure our facility meets the highest standards.

Beyond these two, other relevant examples include Great Wolf Lodge Niagara Falls (Canada) which draws cross-border tourists year-round, West Edmonton Mall’s World Waterpark in Canada (operating successfully since the 1980s inside a mall, demonstrating longevity of indoor tropical attractions), and the Eden Project in the UK (not a water park but large climate-controlled biomes for tropical and Mediterranean plants, showcasing sustainable dome design and educational value). Each of these informs our plan: Great Wolf and West Edmonton show that even in cold, northern locations, indoor water parks can become staple attractions; Eden Project shows how to build and run an ecological indoor environment responsibly. By studying their designs and performance, Watertown can adopt best practices – for instance, using high-efficiency climate control systems that keep operational costs manageable (West Edmonton Mall’s waterpark has high-performance HVAC to handle Alberta winters), or using renewable energy and daylight like Eden’s biomes do.

In summary, the success of Tropical Islands, Kalahari, and others proves that a year-round indoor tropical park can be a major economic driver and visitor magnet. We learn that upfront investment and smart design (often aided by public-private collaboration) are required, and that continuous innovation and marketing are key to sustain attendance. These case studies give confidence that Thompson Park’s transformation is achievable with careful planning and ambition.

3. Funding Sources and Public-Private Partnership Model

Establishing a world-class indoor tropical complex will require a creative blend of funding sources, leveraging both public and private funds. The project’s capital costs will be significant (potentially tens of millions of dollars), so a public-private partnership (PPP) is the most viable approach. Below are potential funding streams and how they can work together:

- Municipal and State Grants: The City of Watertown and New York State can kickstart the project with grants aimed at economic development, tourism, and infrastructure. For example, Watertown has already earmarked $4+ million in federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds for park improvementswwnytv.com – some of this could be allocated to planning or initial site work for the indoor complex, aligning with the goal of year-round park use. New York State’s Regional Economic Development Council (REDC) grants or Empire State Development’s tourism grants (such as the Market NY program) are natural fits; these programs routinely fund attractions that will boost regional tourism and jobs. The project could be pitched as a flagship tourism development for the North Country region, potentially securing a share of state funds dedicated to Upstate revitalization. Additionally, if the Thompson Park complex incorporates significant sustainable features, it can seek grants like NYSERDA’s Building Cleaner Communities Competition which offers up to 60% of project costs (up to $1.7M, or even $2M with geothermal) for projects striving for net-zero emissionsnyserda.ny.gov. Being a recreation facility open to the public also makes it eligible for municipal bonding (e.g., the city could issue bonds for new recreational facilities) which could later be paid back by facility revenues.

- Private Investment and Developers: A substantial portion of funding would come from private investors or a dedicated developer/operator. The city could issue a Request for Proposals (RFP) to attract an experienced water park resort developer (for instance, companies like Great Wolf, Kalahari, or Merlin Entertainment which runs indoor attractions worldwide). A private partner would bring capital and expertise in design/construction and would likely operate the facility under a long-term lease or revenue-sharing agreement. The incentive for private players is the profit from operations over time; the incentive for the city is not having to bear the full financial risk and leveraging private sector efficiency. A possible model is for the city to lease a portion of park land to the developer at a nominal rate, contingent on the developer investing, say, $30–50 million to build and equip the complex. The lease could stipulate public access requirements and perhaps a share of revenue or a PILOT (Payment In Lieu of Taxes) since it’s city land. This way, the asset is developed without the city shouldering all debt, but the public still benefits from guaranteed access and economic activity. Private investors might also include local entrepreneurs (for example, a regional hospitality group) or even a community investment fund if residents want to buy small stakes (a form of crowdfunding local ownership).

- Tourism Development Programs and Tax Incentives: New York State has programs akin to Virginia’s TDFP mentioned earlier. Watertown should explore the state’s Downtown Revitalization Initiative (DRI) or other community development funds – though Thompson Park is not in downtown, the broader impact on the city’s economy might qualify it for competitive funding. Likewise, industrial development agencies (IDAs) in New York can offer tax abatements or low-interest financing for projects that create jobs. A likely scenario is establishing a Tourism Attraction Financing District or utilizing Tax Increment Financing (TIF) at the city level: increased property and sales tax generated by the complex over the baseline could be funneled to repay bonds or loans that financed construction. For instance, the city could issue a bond for infrastructure (parking facilities, road improvements to the park, utility upgrades) and use a portion of new sales tax from ticket sales to service that debt – essentially self-funding from the project’s success. The Spotsylvania Kalahari deal is instructive here: both state and locality agreed to divert future tax revenue from the resort to help the developer pay back loans, reducing the financing burdenspotsylvania.va.us. Watertown could negotiate a similar performance-based incentive: offer the developer a rebate of a certain percentage of sales or bed taxes the complex generates, up to a cap, ensuring the project has cash flow relief in early years while the city still eventually gains net new tax income.

- Green Energy and Sustainability Incentives: Given the emphasis on an eco-friendly design, numerous incentives can be tapped. Federal tax credits for renewable energy (solar Investment Tax Credit, for example) could reduce the cost of installing solar panels on the facility. NYSERDA and National Grid may have grants or rebates for energy-efficient equipment, insulation, heat pumps, etc. If the project includes things like electric vehicle infrastructure (charging stations for visitors, solar-powered shuttles), there are specific programs supporting that. Moreover, as New York pursues climate goals, projects that reduce carbon could get carbon credit funding or inclusion in state pilot programs (like the one offering extra funds for ground-source heat pumpsnyserda.ny.gov). The team should compile a list of all applicable green building grants – these might collectively contribute a few million dollars and also serve as positive publicity (the complex could aim to be a showcase of sustainable architecture).

- Federal and Other Sources: The federal Economic Development Administration (EDA) offers grants for projects that spur job growth in distressed areas – Watertown could make a strong case for EDA funding by highlighting the job creation and the need to diversify the local economy (especially if some traditional industries have declined). Additionally, tourism recovery funds (if any remain post-pandemic) or future stimulus packages might be sources. The city could also consider New Markets Tax Credits if the census tract qualifies, which would attract private investment by offering tax credits in exchange. Another avenue is partnering with the Department of Defense or Fort Drum (if there’s interest in improving soldier and family quality of life, some defense community funds might be accessible, albeit that’s speculative).

In practical terms, a likely financing plan might look like: a combination of city contribution (e.g. land + ~$5M grant), state/federal grants (perhaps $5–10M), and private financing (~$20–30M from the developer or investors), supplemented by smaller green incentives and possibly a financing district. The ownership structure could be such that the city owns the land and possibly the structure (if built with public funds), leasing it to an operator, or the operator owns the facility but agrees to public access terms and revenue sharing. This hybrid public-private ownership ensures the project serves community interests (affordable access for locals, adherence to park regulations) while also enabling profitability.

The public sector’s role is also to underwrite some feasibility studies and design work upfront to de-risk the project for private investors. For instance, paying for an initial architectural design and environmental impact study through grants can accelerate the timeline and make it “shovel-ready” – an attractive prospect for investors or state funding competitions. Public investment in infrastructure (parking lots, road upgrades to handle traffic, extending water/sewer lines, improving electrical grid capacity for the park) is a critical part of the funding too; these costs can be covered by city capital budgets or state DOT funds since they benefit the wider community.

Finally, given the complex’s potential, Watertown could seek designation as a Regional Tourism Anchor and lobby for unique funding. Sometimes large projects get line-item support in state budgets if they are seen as transformative. Building political and public support (with evidence from case studies and economic impact analysis) will be key to unlocking these funding sources. In short, by assembling a mosaic of funding – local ARPA funds, state economic grants, green incentives, private capital, and innovative tax-financing schemes – the city can cover the hefty price tag without overburdening any single source. The result is a true partnership where all stakeholders invest in the vision and share in the rewards.

4. Business Model and Economic Projections

A solid business model will ensure the indoor tropical complex is financially sustainable in the long run. Below are projections and considerations for operating costs, revenue streams, pricing, and economic impact:

Operating Costs: Running a tropical water park of this scale will incur substantial operating costs. The largest expenses are likely to be energy (heating the air and water), staffing, and maintenance. We can estimate that several hundred employees will be required for full operations. For example, Tropical Islands employs ~600 people for its massive facilityen.wikipedia.org; our complex might be slightly smaller, so perhaps 200–300 full-time equivalent jobs will be created on-site (including lifeguards, facility managers, maintenance crew, horticulturalists for the botanical garden, security, guest services, food & beverage staff, etc.). Labor costs will thus be a significant portion of the budget, but they also represent local job creation. Energy costs can be mitigated by the sustainable design (see Section 5) – using efficient heat pumps, solar power, and waste-heat recovery will reduce reliance on fossil fuels. Nonetheless, maintaining ~80°F inside during a North Country winter will require a robust HVAC system. We should plan for a dedicated operations and maintenance (O&M) fund for the complex, likely partly covered by the private operator. Other costs include water and filtration chemicals, insurance, marketing, and periodic refurbishment of attractions (water park equipment has to be inspected daily and major components like slides might need resurfacing every few years). We anticipate that initial years might run at a slim profit or even a managed loss as attendance ramps up (Tropical Islands, for instance, lost €10–20M in its first year due to lower than expected attendanceen.wikipedia.org). Therefore, the business model should include a reserve fund or guarantees to cover any early shortfalls – perhaps the private partner will ensure this or the city can structure contingency support (with limits) to get through the ramp-up period.

Revenue Streams: The complex will have multiple revenue streams to support its operations:

- Admission Fees: The primary income will be from ticket sales. We expect to offer day passes to tourists and casual visitors, as well as membership or season passes to local residents. For context, Tropical Islands’ day ticket is about €53–64 (≈ $60–70) for an adulttropical-islands.de, and Kalahari charges around $50–$100 per person per day (often packaged with hotel stays). We would set a competitive price that balances accessibility with revenue needs. Perhaps a local resident adult day pass could be ~$30–$40, and non-resident or peak time pass ~$50–$60. Children might be ~$20–$30. Offering family bundles and discounts for Jefferson County residents will ensure the park is accessible to the community (a crucial aspect since public funds support it). A season pass (annual membership) for locals at, say, $200 per person or $500 per family could provide steady upfront revenue and encourage frequent use.

- Food and Beverage Sales: With at least one sit-down restaurant and a couple of cafes/snack bars inside, food and drink can generate significant income (often at healthy profit margins). Visitors might spend $10–$20 per person on food on average. We can maximize this by offering unique dining experiences, like a café in the rainforest section or a poolside smoothie bar, and possibly allow catered events or birthday party packages that include food.

- Merchandise and Rentals: Gift shops selling tropical-themed merchandise, local souvenirs, swim gear, etc., will add to revenue. Likewise, locker rentals, towel rentals, and cabana rentals (private small huts or seating areas by the pool that families can rent for a day for a premium fee) can bring in income. Many water parks charge for premium seating or fast-pass access to slides; we could consider a small upcharge for a “fast lane” or exclusive experiences, though this should be balanced against inclusivity.

- Special Events and Programs: The facility can be rented or used for special events – for instance, corporate events, school field trips, or even tropical-themed winter parties. Imagine local companies holding an employee appreciation day in January at the indoor beach, or schools bringing kids for educational tours of the botanical garden with a fun swim included. Such group sales can be priced at a group rate. We can also host indoor surfing competitions, holiday events (a “Tropical Christmas” festival under the dome), or partner with local tourism bureaus to create packages (e.g. “Weekend Getaway – indoor tropics and a visit to the nearby ski mountain for contrast”).

- Hotel/Accommodation Revenue Sharing: If an on-site lodging component or a partnership with local hotels exists, there may be revenue-sharing or referral fees. For example, if a local hotel offers a “Stay and Play” package, part of that revenue flows to the park.

- Sponsorships and Naming Rights: As a creative funding/revenue boost, the city could seek a naming sponsor for the facility or its components. Perhaps a major company (maybe a green energy company or local bank) might pay for naming rights of the complex or specific areas (e.g. “XYZ Corp Wave Pool”). This would provide an upfront or annual sponsorship fee which can support operations. Advertising within the park (tastefully done, e.g. sponsor logos on slides or a video screen) could also generate minor income.

Considering attendance: We should model a range of scenarios. In a steady state, perhaps the complex could attract on the order of 200,000–300,000 visitors per year. This assumes on average ~600-800 visitors per day, with peaks into a few thousand on holidays. (For comparison, Tropical Islands eventually exceeded 1 million annual visitorsen.wikipedia.org, but that’s a larger facility near Berlin; our target is more modest given Watertown’s smaller market, though drawing from tourists driving on I-81 and Canadian visitors could boost numbers). If 250,000 visitors spend an average of $50 each (including ticket and in-park purchases), that’s about $12.5 million annual gross revenue. This is a rough figure – actual revenue could be higher if tourism really takes off, or lower in initial years. The business plan should incorporate conservative estimates (perhaps assume 150,000 in year 1, 200,000 in year 2, etc.) and a breakeven analysis.

Profitability will depend on controlling costs and hitting attendance/revenue targets. Economies of scale help – many costs (lifeguards, running pumps, etc.) are relatively fixed regardless of whether 200 or 500 people are in the park on a given day. So maximizing attendance, especially on off-peak days, is important. The park can introduce dynamic pricing and promotions: e.g. deep discounts for locals on weekdays, or evening tickets (a reduced “evening rate” for say 4-8pm to get a second wave of visitors in one day). Tropical Islands did something similar by adjusting ticket structures and adding overnight stays to attract more people from farther awayen.wikipedia.org. We will also aim for year-round balance: summer might actually be a quieter time (since people can swim outdoors in natural venues), whereas fall, winter, and spring could be busy. To boost summer usage, we could open portions of the complex to the outside – e.g., open big side doors on nice days, or have outdoor lounge areas – so it complements, rather than competes with, the great outdoors.

Economic Impact and Job Creation: The direct business of the park is one side; the broader economic impact on Watertown is equally important. By conservative estimates, hundreds of direct jobs will be created at the facility (from entry-level service jobs up to management and technical positions). Indirectly, local businesses should see a surge in activity: hotels will get bookings from tourists coming specifically to visit the complex (especially in winter when normally tourism is slow), restaurants and shops in Watertown may see more customers (tourists who spend a day at the park might dine in town or visit other attractions like the historic downtown or Sackets Harbor nearby). The city and county will benefit from sales tax revenue on tickets, food, and merchandise sold, as well as bed taxes from increased hotel nights. If structured properly, the complex will also pay property taxes or equivalent – since it’s a public-private venture, perhaps a PILOT agreement ensures the city gets some yearly payment in lieu of property tax (unless it’s fully city-owned). In Spotsylvania’s Kalahari projection, the resort was to become the largest taxpayer, indicating how such a project can bolster local government financesspotsylvania.va.us.

We can look at multipliers: the construction phase itself will create construction jobs and utilize local contractors (subject to the specialized dome construction, which might involve outside experts). Once operational, spin-off businesses might emerge – e.g., tour operators packaging the water park with other regional destinations, or new entertainment venues popping up to capture visitors (maybe an entrepreneur opens a tropical-themed B&B or a new restaurant downtown because of the increased tourist flow). The park could also deepen the Fort Drum connection by providing a leisure outlet for soldiers and their families, potentially making the base a more attractive posting and indirectly aiding retention and morale (hard to quantify, but a community asset like this adds to quality of life, which has economic value).

In terms of pricing strategy, we have to balance affordability for locals with the need to cover costs. A possible model is a two-tier pricing: local residents (with ID or membership) get a discounted rate, while tourists pay standard rates. Additionally, offering certain community days or hours (e.g. one evening a week, local youth groups or schools get in free or very cheap) can ensure equitable access – this can be subsidized by either city funds or by the higher tourist revenues. This approach fosters goodwill and meets the mandate that it’s “accessible to both locals and tourists.”

To summarize the business outlook: with a strong regional draw, the Thompson Park indoor tropical complex could generate on the order of $10–15 million in annual revenue once established, against perhaps $8–12 million in annual operating costs (very rough figures). This should allow for a healthy operation, reinvestment in new features, and returns for the private partner, while also delivering economic benefits locally. Of course, detailed feasibility studies will refine these numbers. The key is that the concept is not just a public amenity but a self-sustaining enterprise that will pay back initial investments over time. By year 5 of operation, we’d aim for the facility to be solidly profitable, enabling profit-sharing with the city or further expansions (like adding a new slide, or maybe an outdoor water adventure course) to keep the park fresh. And beyond the ledger, the social ROI is high: the community gains a year-round recreation spot, youths have a safe and fun place to go (potentially reducing winter doldrums and even health issues by encouraging active play), and Watertown’s image gets a huge boost as a place with unique attractions.

5. Environmental Sustainability and Energy Efficiency Plan

Environmental stewardship is a cornerstone of this project – both to honor Thompson Park’s natural legacy and to keep operating costs and ecological impact in check. The vision is to create one of the greenest indoor water parks in the world, showcasing how recreation and sustainability can go hand in hand. Key components of the sustainability plan include:

Eco-Friendly Building Design: The complex will be designed for energy efficiency from the ground up. The dome or building envelope should use high-performance insulation to minimize heat loss during winter. Materials like ETFE foil or double-pane glass in the roof will allow sunlight and UV in (for plant growth and natural illumination) but are excellent at retaining heat (ETFE is essentially transparent insulation and very lightweight). As mentioned, Tropical Islands had to retrofit ETFE panels to help their plantsen.wikipedia.org; we will integrate this from the start, essentially having a huge “sunroof” over the tropical forest and pool areas. The structure can also use thermal mass (perhaps incorporating a concrete foundation or water features that store heat) to even out temperature fluctuations. We will pursue a LEED Gold or Platinum certification for the building, signaling the highest standards in sustainable design – including rainwater harvesting, low-flow fixtures, and non-toxic building materials.

Renewable Energy Integration: A combination of on-site renewables will power a significant portion of the facility:

- Solar Energy: The expansive roof or nearby open land (like possibly the park’s maintenance areas) can host a large array of solar photovoltaic panels. Though the dome itself might be largely translucent, we can integrate solar panels on any opaque sections or adjacent structures (parking canopy solar panels, for instance). These panels will generate electricity to run pumps, lights, and even supplemental electric heating. Additionally, solar thermal collectors (technology that heats water directly from sunlight) could be used to warm the pool water or feed into the climate system – sunny winter days could contribute a lot of heat. New York offers incentives for solar, and net metering can feed excess summer power to the grid in exchange for credits to use in winter.

- Geothermal Heating/Cooling: We will strongly consider a geothermal heat pump system. This involves drilling wells or laying coils underground to use the earth’s stable temperature for heating and cooling. In winter, the geothermal system can capture heat from the ground to help warm the dome’s air and water, using much less electricity than conventional boilers. In summer, it can do the reverse, cooling and storing heat back underground. Given Thompson Park’s open land, horizontal ground loops could be feasible, or vertical boreholes if space is limited. The NYSERDA program cited earlier specifically boosts funding for projects using ground-source heat pumpsnyserda.ny.gov, which we could tap. Geothermal can likely handle base-load heating, with high-efficiency gas or electric boilers as backup for the coldest days.

- Waste Heat Reuse (AI Server Farm Synergy): Perhaps the most exciting synergy is utilizing the waste heat from the planned AI server farm in Watertown. Data centers produce enormous amounts of heat as a byproduct of cooling their servers. Instead of letting that heat dissipate unused, we can build a pipeline or district heating connection to channel it into the tropical complex. This concept has real precedent – in the UK, a pilot project used a small data center’s output to heat an indoor public pool, cutting the pool’s gas use by 62%theguardian.com. Large tech companies have also partnered with communities to reuse data center heat for heating buildings. In our case, the AI server farm (which might be located at an industrial park in town) could have a heat exchanger system: warm water or air from the server cooling gets piped to the park to help heat the pools or air, then returns cooled to the servers (cooling them in the process). It’s a symbiotic relationship: the park saves on heating costs and emissions, and the data center saves on cooling costs. We would explore an agreement where the data center (perhaps operated by a private tech company or the DOD if at Fort Drum) supplies low-grade heat at low or no cost, which dramatically reduces fossil fuel use for the tropical dome. Technically, this might involve a buried insulated water line running a few miles – an upfront infrastructure cost that could be shared between the data center operator, the city, and the park. Given the growing push for sustainable AI, this could become a showcase project (imagine headlines about AI and recreation powering each other).

- Wind Energy: Thompson Park is elevated and could potentially be a site for small-scale wind turbines, if acceptable. Even a single medium-size turbine on the park’s west side could generate power (though visual and wildlife impacts would need consideration). If not on-site, we could procure green power from a nearby wind farm (Jefferson County has wind resources) or the city’s municipal power could allocate hydroelectric power from the Black River to run the complex. Committing to 100% renewable electricity (via onsite generation + green purchasing) would align with Watertown’s tech-forward, climate-forward image.

Water Conservation and Quality: Water parks use a lot of water, but most of it is continuously filtered and recirculated rather than consumed. We will implement advanced filtration and water recycling systems. All pool water will circulate through high-efficiency filters (possibly regenerative media filters that waste less water) and UV sterilization (to minimize chemical use). Rainwater harvesting from the roof can supply water for the pools and irrigation for the plants – large storage tanks will collect rain and snowmelt, reducing reliance on city water. We can also recycle greywater (like shower water after filtering) for use in toilets or irrigation. The botanical garden aspect actually helps here: plants can be integrated into a system to naturally treat and absorb some wastewater (constructed wetlands idea) before it’s reused or released, adding an educational element about water recycling. By monitoring water chemistry with automated systems, we ensure minimal discharge – ideally, the facility would have zero stormwater runoff (all captured) and near-zero wastewater output (almost all water is reused or evaporated). The small amount of water lost to evaporation from pools will add humidity which helps the plants, and makeup water needed will be far less than, say, a conventional water park due to these efficiencies.

Green Materials and Biodiversity: Construction will use sustainable materials where possible. For example, using Glulam (glue-laminated) timber or recycled steel for structural elements can lower the carbon footprint. If any wood is used decoratively, it will be from certified sustainable forests. Inside the dome, the landscaping will use organic methods (no pesticides that could harm visitors or plants). We could partner with local environmental groups or the Thompson Park Conservancy (which runs the zoo) to possibly incorporate a butterfly house or small animal exhibits (maybe tropical butterflies or fish aquariums) as part of the botanical garden – this enhances biodiversity and education. Ensuring the indoor ecosystem is healthy is crucial, and that involves selecting appropriate plant species that thrive indoors and using integrated pest management to avoid any infestations without harmful chemicals.

Waste Reduction: The operation will aim to be zero-waste or close to it. This means extensive recycling and composting programs on-site (food waste from the café can be composted – perhaps used to fertilize the indoor plants!). Single-use plastics will be minimized; for instance, concession stands might use reusable cups with a deposit, or compostable dishware. There can be water bottle refill stations to discourage disposable bottles. The gift shop could sell sustainable merchandise, and even the staff uniforms could be made of recycled fabric, as part of the ethos.

Transportation and Access: To further green the project, we encourage eco-friendly transportation. Install EV charging stations at the parking area to promote electric cars. Work with the city to ensure there’s public transit or shuttle service from downtown/major hotels to Thompson Park, potentially using electric shuttles or even an autonomous vehicle shuttle (more on that in the next section) – this reduces traffic and emissions. For local residents, improving walking and biking paths to the park encourages people to come without a car when possible.

Integration with Nature and Park: Although we are building a large structure, the surrounding parkland will be respected and even enhanced. We can create an outdoor native species garden around the facility, planting trees and shrubs that blend the dome into the landscape. Green roofs on any low-rise portions of the building (like over locker rooms or the restaurant if those are one-story annexes) will reduce runoff and provide habitat for birds and pollinators. Light pollution will be controlled (the dome will likely glow at night, but we ensure lighting is downward-directed and uses spectrum that is less disruptive to wildlife). The goal is that outside the dome, the rest of Thompson Park remains a natural oasis – hikers and picnickers should still find tranquility. In fact, some might enjoy walking outside and then popping into the tropical dome for a warm-up on a winter day.

In pursuit of these sustainability goals, we will seek expert guidance (perhaps from firms that worked on the Eden Project or other green buildings). We’ll also measure performance: the complex can have a dashboard display for visitors showing real-time energy generation, water saved, etc., turning the facility itself into a demonstration of green technology. This educational aspect can inspire others and fits the tech-forward theme of Watertown. With all these measures, we aim for the complex to be as close to net-zero energy and carbon-neutral as feasible. Any remaining emissions (maybe from backup boilers or vehicle trips) could even be offset via local tree planting or purchasing carbon credits, making the tropical paradise not only economically beneficial but also environmentally responsible. By designing thoughtfully, this project can actually enhance the environment – both by reducing the need for locals to drive hours to find winter recreation (thus cutting emissions) and by possibly providing a sanctuary for plants and small animals.

In essence, the indoor tropical complex will be a showcase of sustainability: from its energy source to its daily operations. This not only reduces costs (green design is an investment that pays off in lower utility bills) but also positions Watertown as a leader in green development, attracting positive attention and maybe even eco-tourism. It’s a perfect complement to the city’s tech aspirations – high-tech, green-tech, and recreation all woven together.

6. Synergy with Watertown’s Tech Hub Transformation

Watertown is charting a course to become a tech-forward hub, as evidenced by initiatives like the development of an AI server farm and an autonomous vehicle (AV) testing zone in the area. It’s crucial that the Thompson Park tropical complex ties into this broader transformation, creating a mutually reinforcing relationship between the city’s tech sector growth and its recreational/tourism growth.

Utilizing AI and Smart Technology: The indoor park itself will leverage cutting-edge technology (a fitting showcase in a city embracing AI). For instance, we can implement an AI-driven building management system that optimizes energy use – adjusting heating, lighting, and ventilation in real-time based on occupancy and weather forecasts. AI algorithms could learn the facility’s patterns and shave off energy peaks, further enhancing our sustainability plan. Additionally, AI-powered monitoring could assist with safety: cameras with computer vision might help lifeguards by detecting if someone is in distress in a pool (as an augment to human staff, some water parks have begun exploring this). Even for horticulture, AI sensors could monitor plant health and automate watering schedules. By integrating these, the complex becomes a living lab for smart building tech – something that can attract interest from tech companies and universities. We can partner with local tech talent (maybe Fort Drum’s technical units or Jefferson Community College’s programs) to maintain and innovate these systems, thus creating a bridge between the recreational facility and the tech community.

Autonomous Vehicle Integration: If Watertown is hosting an autonomous vehicle test zone (perhaps on certain streets or a dedicated track), we can collaborate to incorporate AVs into the visitor experience. One idea is to operate an autonomous shuttle service from downtown or key parking areas to Thompson Park. Visitors could hop in a self-driving electric shuttle (maybe a small 6-8 person pod) that ferries them to the park entrance. This would not only be practical (solving “last mile” transit and reducing parking demand at the park) but also serves as a public demonstration of the city’s AV technology in action. It becomes part of the attraction: a tourist might come to Watertown for the water park and end up riding in a driverless shuttle, experiencing two innovations at once. The AV test zone could also use the park’s off-hours for testing in winter conditions – for example, after the park closes at night, the large parking lot could be a safe area to test autonomous snowplows or shuttle navigation in a controlled environment. By coordinating schedules and needs, both the park and the AV initiative benefit.

Data Center Heat Partnership: As discussed, linking the AI server farm’s waste heat to the complex’s heating system would be a tangible symbol of tech-community synergy. Beyond the engineering, it sets up a narrative: “The servers training AI models for the future are keeping our tropical lagoon warm.” This kind of integration might draw media attention and could even attract funding (from programs that like to see cross-sector collaboration). Moreover, it gives the data center a positive community role (rather than being seen as just a big power consumer or a fenced-off facility). The operation of transferring heat would involve collaboration between the facility managers – maybe even an AI system balancing the heat exchange – again an opportunity for local innovation.

Collaborative Innovation Hub: The park complex could house a small exhibit or innovation center that highlights Watertown’s tech and sustainability projects. Perhaps in the lobby or mezzanine, there’s a display about the AV test zone, the AI server farm, and any local tech startups. One could imagine an interactive screen where visitors learn about how AI works or how autonomous vehicles sense the environment – educational content that complements the leisure aspect. If the city is pushing STEM education (as many tech hubs do), the complex can host STEM field trips or hackathons in a dedicated multipurpose room. For instance, a robotics competition could be held in the off-season using a corner of the dome or a nearby space – students compete in view of that inspiring indoor rainforest. This blurs the line between fun and learning, making the complex a community science center in addition to a water park.

Attracting Talent and Investment: A tech hub isn’t just about having tech infrastructure; it’s about attracting skilled workers and companies. Quality of life plays a huge role in that. By having a unique attraction like this tropical park, Watertown significantly ups its appeal to potential tech employees. Imagine a young software engineer considering a job in Watertown – knowing that on weekends they can take their family to a world-class indoor tropical paradise or enjoy high-tech amenities in a small city could tip the scales in favor of relocation. It sends a message that Watertown is forward-thinking and dynamic. The development itself might draw interest from tech investors – for example, companies that build smart sensors or IoT devices might see the park as a testbed (deploying their newest gadget to monitor plant soil moisture or crowd flow). Partnerships can be formed so that new tech is piloted at the park before commercialization, leveraging the fact that the complex is city-affiliated and open to collaborations.

Marketing and Branding Synchronicity: The city can brand this development in tandem with its tech initiatives. Possibly a unified campaign like “Watertown: Innovation and Recreation Combined” or “Where Winter Meets the Tropics – Powered by Technology”. Joint press releases about the autonomous shuttles serving the water park, or the AI managing energy, will reinforce the narrative. For tourists, Watertown could position itself as not just a gateway to the Thousand Islands or Adirondacks, but as a distinct destination where one can experience the future (tech) and have fun. This interplay might draw new demographics: tech conferences could consider Watertown precisely because attendees might want to bring families to enjoy the park while they attend business (the convention center in Kalahari model – though if we don’t build a full convention center, we could still host smaller tech summits in town and use the park as part of the venue or social event).

Smart City Integration: If Watertown is indeed building out “smart city” infrastructure (common in tech hub plans), the park can integrate with that. For example, a city app could show real-time info on park attendance or allow residents to reserve a time slot (managing flow via digital means). The parking system could have sensors to guide drivers (or autonomous vehicles) to available spots, reducing idling and congestion. And data collected (anonymously) from the park’s operations could feed into city analytics – like energy usage patterns, which can inform the city grid management in coordination with the data center and other users.

In essence, the indoor tropical complex will serve as a physical and symbolic bridge between Watertown’s emerging tech economy and its community/tourism economy. It embodies the idea that high-tech progress can directly improve quality of life. By weaving in autonomous transport, AI energy systems, and data center collaboration, the project becomes more than just a water park – it becomes a showcase for what the future can look like in a small city setting. Watertown can demonstrate how even a city of its size can integrate advanced technology into daily life in a fun, accessible way. This synergy could attract further grants or designation (for instance, New York State might highlight Watertown as a model “Smart City Recreation Project”).

Finally, tying into the tech hub vision ensures broad support: those in favor of economic tech development see the benefit of a recreational draw for employees and families, while those focused on community development see the benefit of tech contributions to making the facility sustainable and cutting-edge. The result is a virtuous cycle: tech investments help make the tropical park a success (through heat sharing, smart systems), and the tropical park helps draw more people and attention to Watertown’s tech scene.

7. Actionable Next Steps for Implementation

To turn this ambitious plan into reality, city leaders and potential private partners should undertake a series of clear next steps. Below is a roadmap of actionable steps to move the project forward:

- Feasibility Study and Market Analysis: Timeline: Months 1-3. The City of Watertown should commission a comprehensive feasibility study. This will refine cost estimates, project the attendance and financial performance in detail, and assess site-specific factors (soil conditions, utility capacity at Thompson Park, etc.). It should include a market analysis surveying regional residents and tourists to gauge interest, and studying competitors (nearest water parks, etc.) to solidify the unique selling points of this complex. This study will provide the data to support grant applications and investor pitches. Funding for this could come from the already allocated ARPA funds or a small state planning grant.

- Community and Stakeholder Engagement: Timeline: Months 2-4 (overlapping). Early on, hold public forums and workshops with local residents, Thompson Park conservators, and other stakeholders (Fort Drum representatives, tourism boards, etc.). Present the concept and listen to feedback or concerns. Engage groups like Friends of Thompson Park (who helped with the master plan) to ensure the design aligns with community values. Transparency and inclusion now will build public support and help address any controversies (for example, if there are concerns about traffic or preserving green space, these can be mitigated in the plan). Additionally, reach out to the operators of Tropical Islands, Kalahari, and Great Wolf for informal discussions or advice – industry insights are invaluable.

- Site Selection and Land Use Approvals: Timeline: Months 3-6. Determine the exact footprint within Thompson Park for the complex. Likely the underutilized western side or near the old reservoir as discussed. Work with city planners to check zoning or any legal restrictions (public parkland in NY sometimes requires state legislative approval for long-term leasing or “alienation” – if needed, begin that process by drafting a request for legislative approval to use X acres of the park for this public-private recreational facility). Conduct an initial environmental review (sunlight analysis, impact on park wildlife, etc.) to shape design choices. At this stage, also plan where parking will go (perhaps expand existing park lots or create a new lot with minimal tree removal). Secure any necessary state environmental quality review (SEQR) filings early, as large projects require this.

- Conceptual Design and Master Planning: Timeline: Months 4-8. With feasibility in hand, engage an architectural firm (preferably one with experience in indoor water parks or large-span structures) to create conceptual design renderings and layout plans. This should cover the dome design, interior zoning (where pools vs. garden vs. slides will sit), and integration with the park landscape. These renderings will be crucial for fundraising – they help everyone visualize the end product. Concurrently, develop a phasing plan: it might be possible to build the complex in phases (for example, first the core water attractions, later an expansion of the botanical garden or an attached greenhouse) if funding comes in stages. But ideally, plan it as one project for efficiency. Include engineers in this phase to outline the HVAC, structural, and civil engineering approaches (especially for the sustainable systems like geothermal and the data center heat link, we need engineering studies). If the AI server farm is on board, coordinate with their engineers now to map out the heat exchange logistics.

- Identify and Secure Funding:Timeline: Months 6-12. With a fleshed-out plan and visuals, begin the heavy lifting of funding:

- Public Funding: Prepare applications for relevant grants. For example, apply to the next round of the Regional Economic Development Council for a significant grant (highlight tourism impact and regional job creation). Apply to NYSERDA’s net-zero building competition (noting the July 2024 deadlinenyserda.ny.gov if still applicable, or subsequent rounds). If Downtown Revitalization funds or federal EDA funds are available, submit proposals. Also, approach state legislators and make the case for a line item in the state budget or a multi-agency funding package – having community support and a strong feasibility report will help here. This step involves a lot of proposal writing and pitching, which the city’s planning/development department can lead, possibly hiring a grant consultant for assistance.

- Private Partner Solicitation: Issue a formal RFP or RFQ (Request for Qualifications) to find a private developer/operator. This document will outline the project vision, the city’s contributions (land, some capital, tax incentives), and ask for interested parties to submit their credentials and concept. Likely candidates include known water park resort companies or large theme park operators. Also, local or regional investors might form a consortium to respond. Promote this opportunity at tourism investment conferences or through economic development networks. Once responses come in, evaluate partners based on experience, financial capability, and their proposed business terms. Choose a partner and negotiate a preliminary Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) that covers roles, contributions, and profit-sharing principles.

- Finance Plan Finalization: Work out the mix of funding based on what grants look promising and what the private partner can commit. If needed, prepare a plan for a municipal bond referendum or seek City Council approval to bond a certain amount (tied perhaps to specific infrastructure like a new access road or utility improvements). Also explore New York’s Industrial Development Agency financing – Jefferson County’s IDA might issue bonds on behalf of the project for tax-exempt financing. All these pieces should come together in a finance package that closes the gap to reach the total project budget.

- Formalize Public-Private Partnership Agreement: Timeline: Months 12-15. With funding prospects lined up and a preferred developer on board, negotiate a detailed Development Agreement. This should spell out: project scope, timeline, who pays for what, ownership structure, lease terms, how revenue will be split or how rent is calculated, public access guarantees (e.g. pricing controls or number of community discount days), and contingency plans (what if attendance is lower, etc.). Also include clauses about maintaining the facility to certain standards, and processes for future expansions or upgrades. This agreement likely will need City Council approval and possibly state review (especially if parkland is being leased). Aim to sign this agreement once all major funding is confirmed.

- Detailed Design and Regulatory Approvals: Timeline: Months 15-24. Now the chosen developer and design team can proceed with detailed architectural and engineering design. This includes blueprints, specifying materials, integrating all systems. At this stage, also conduct the full Environmental Impact Assessment as required (traffic study for how many cars/buses will come, noise analysis – though indoor, but construction noise considerations, etc., and mitigation plans for any impacts). Submit site plans to the City Planning Board for approval, and obtain any needed variances or permits. Coordinate with the Department of Health on pool regulations (they’ll need to approve the water treatment systems for public swimming), and with the State Department of Environmental Conservation if any wetlands/streams are affected (likely not since it’s on a hill, but any water discharge permits, etc.). Also work with the state on any building code waivers for the unique structure as needed. By the end of this step, you should have shovel-ready plans and all permits in place.

- Groundbreaking and Construction Phase: Timeline: Months 24-36 (start construction by year 2). Prepare the site (relocate any park features if needed, do excavation). Aim for a groundbreaking ceremony to generate buzz, inviting local press, state officials (who provided grants), and community members. Construction will likely take 18-24 months. It will involve erecting the dome structure, installing pools and slides (often those are fabricated by specialized companies and assembled on-site), planting the interior landscaping, and building the supporting facilities (entrance building, restaurants, etc.). Given our climate, plan construction smartly around seasons – perhaps foundation work in summer, dome erection before heavy winter, interior work through winter under the enclosed shell. Throughout construction, maintain communication with the public – provide updates, maybe live cams of the dome rising (it’s intriguing engineering!). Also, initiate hiring plans with local job fairs a few months before opening, so staff are trained and ready.

- Testing and Commissioning: Timeline: Months 36-42. Once construction is complete, spend a few months on testing. Fill the pools and test filtration, grow in the plants (likely some plants will be placed earlier to establish), test all rides for safety, and fine-tune the climate control systems (ensure we can reach that 80°F even on a cold day efficiently). During this period, also finalize operational protocols, emergency plans (work with local EMS and fire on emergency response plans inside the dome), and stock the restaurants/shops. Possibly do a soft opening or limited previews – e.g. invite city employees or park donors for a trial day – to get feedback and ensure everything runs smoothly.

- Grand Opening and Marketing Launch: Timeline: around Year 4. Host a grand opening event, inviting media from across New York and influencers in travel/tech spaces. Leading up to this, a robust marketing campaign should launch. This might involve digital marketing highlighting “Tropical Paradise in Upstate NY,” collaborations with regional tourism bureaus (e.g. “Come to Watertown – where you can ski one day and surf indoors the next!”), and outreach to tour operators. Ensure signage on major highways is in place (I-81 should have attraction signs for the park exit). Tie the opening into the narrative of Watertown’s renaissance – perhaps have a ribbon cutting with both a surfboard and a circuit board motif to symbolize recreation and tech together.

- Monitor, Improve, Expand: Timeline: Year 4 onward. Once open, the work isn’t done. Continuously monitor performance vs. projections – if attendance is lower in certain months, adjust marketing or consider new promotions. Gather visitor feedback frequently and iterate: maybe the need arises for another slide or a bigger changing room – plan those improvements as needed. Keep an eye on technology improvements: for instance, if in a few years solar panel efficiency jumps or battery storage becomes cheap, consider adding those to further cut energy costs. Also, program new events (host an annual winter festival, or partner with Fort Drum for military family days, etc.). In a few years, if things go well, consider Phase 2 expansions: maybe an outdoor water play zone for summer (a splash pad or a zip-line course in the park), or adding more wellness facilities (like a gym or more spas) to attract different user groups. Always align these with the broader Watertown strategy – e.g. if the tech hub grows, maybe create a co-working space or café with Wi-Fi in the dome so remote workers can enjoy a tropical surrounding while working (a bit fanciful, but who wouldn’t want to send emails from a pseudo-beach?). Essentially, ensure the complex remains a dynamic asset.

By following these steps, city leaders can navigate the project from concept to reality methodically. It will require diligent project management and collaboration at every level – city officials championing it, private partners executing, community supporting, and higher government funding it. Breaking it into these actionable phases helps make a grand idea achievable.

Watertown stands at a crossroads of opportunity: the chance to marry its high-tech aspirations with a bold quality-of-life project. Step by step, this plan can transform Thompson Park into a landmark destination that symbolizes the city’s evolution. The indoor tropical recreation complex can very well become the crown jewel of Watertown’s transformation – where residents and visitors alike can experience a slice of the tropics powered by the innovations of the north. With careful planning and cooperative effort, this world-class complex can be delivering waves, smiles, and economic growth within a few short years, solidifying Watertown’s reputation as a forward-thinking and vibrant community.

Sources:

- Tropical Islands Resort description and featuresen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org

- Tropical Islands operational facts (capacity, employees, climate)en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org

- Tropical Islands development and funding (hangar purchase and subsidy)en.wikipedia.org

- Tropical Islands initial attendance and profitability challengesen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org

- Tropical Islands ETFE roof adaptation for plant growthen.wikipedia.org

- Kalahari Resorts scale (indoor waterpark square footage)en.wikipedia.org

- Kalahari Spotsylvania public-private financing and projectionsspotsylvania.va.usspotsylvania.va.us

- Kalahari Spotsylvania expected jobs and tax revenuespotsylvania.va.usspotsylvania.va.us

- Watertown Thompson Park master plan emphasis on nature and year-round usewwnytv.comwwnytv.com

- Example of data center heat reuse in swimming pools (Deep Green pilot in UK)theguardian.comtheguardian.com

- Tropical Islands ticket pricing (EUR)tropical-islands.de

- NYSERDA Carbon Neutral Community program detailsnyserda.ny.govnyserda.ny.gov